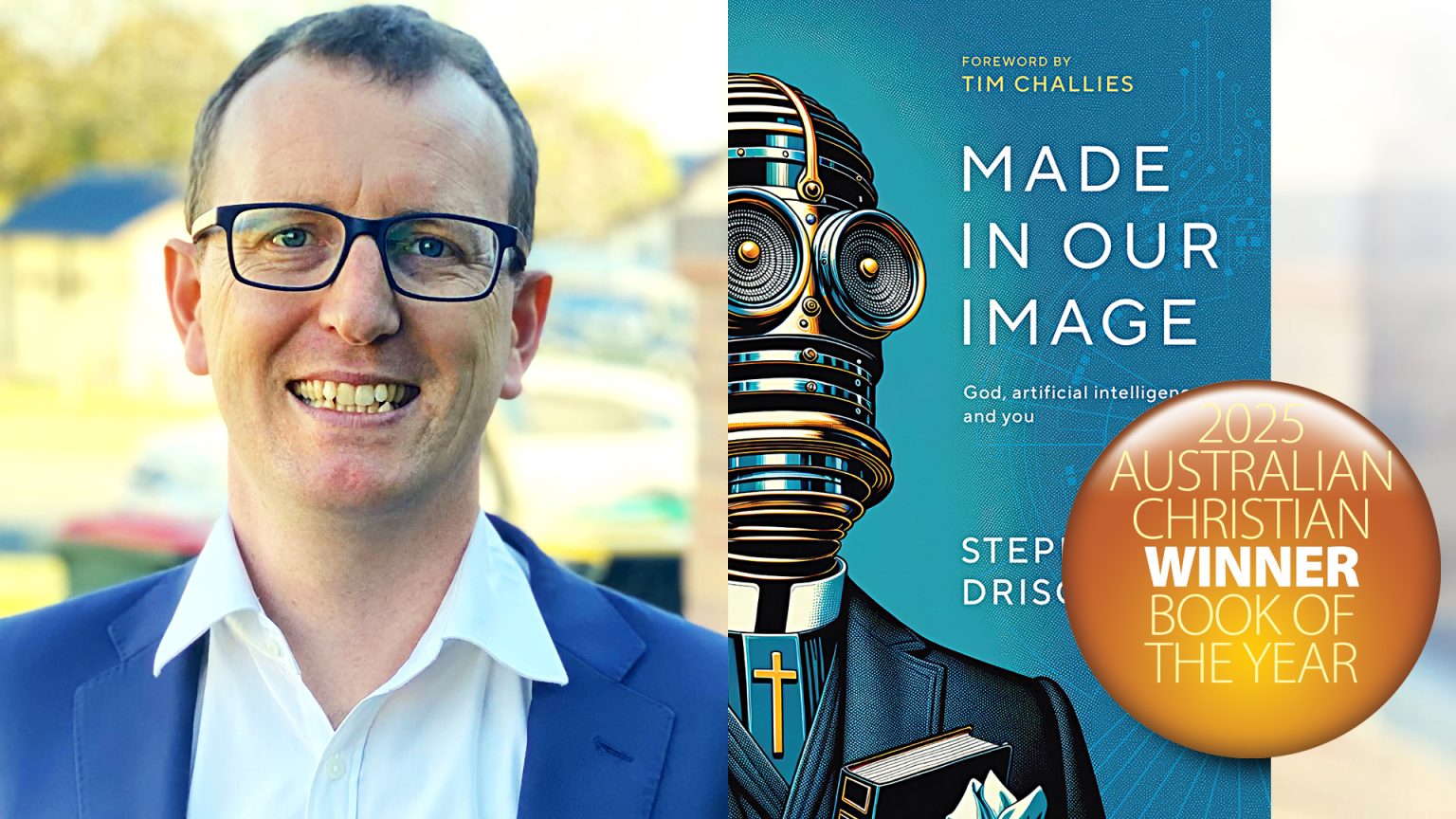

With gracious permission from the author Stephen Driscoll and the publisher Matthias Media, we are pleased to bring you an excerpt from the winning book of SparkLit’s Australian Christian Book of the Year Award for 2025. Our warmest congratulations to both! If you would like to buy the book, it is available from bookshops and can be bought directly from the publisher here. The excerpt is from a chapter about how an understanding of the doctrine of sin relates to our understanding of AI.

Made in Our Image:

God, Artificial Intelligence and You

Stephen Driscoll

Matthias Media

ISBN 9781922980199

from pages 98-101

Debauchery and artificial intelligence

Yann LeCun is a French computer scientist who has been remarkably relaxed about the long-term dangers of artificial intelligence. He argues, “There is no reason for AIs to have self-preservation instincts, jealousy, etc. … AIs will not have these destructive ‘emotions’ unless we build these emotions into them”.1 Similarly, Nick Bostrom argues:

There is no reason to expect a generic AI to be motivated by love or hate or pride or other such common human sentiments: these complex adaptations would require deliberate expensive effort to recreate in AIs.2

Unfortunately, soon after Bostrom and LeCun made these statements, OpenAI trained an artificial intelligence filled with all sorts of destructive emotions.

Why is this the case, and how does this work?

To train a large language model like the one that undergirds ChatGPT, you need an enormous amount of written human expression. When I say enormous, I mean enormous. The free version of ChatGPT at time of writing (GPT-3.5) is trained on roughly a hundred times as much written language as you would get if you downloaded the entirety of Wikipedia.3 The paid version (GPT-4) has been trained on a language file more like two thousand times the size of Wikipedia.4

So, what were these models trained on? The exact mix for GPT-4 is a company secret. The training dataset sections of LLM papers are vague, perhaps intentionally so. A similar model, Chinchilla, released in 2022, was trained on six datasets, which are labelled ‘Massiveweb’, ‘Books’, ‘C4’, ‘News’, ‘GitHub’ and ‘Wikipedia’.5 ‘Massiveweb’ is the largest file and includes a large ‘scrape’ from the internet. The ‘Books’ file presumably includes an enormous collection of digital books. ‘News’ is presumably a dataset of publicly available news. ‘GitHub’ is a large database of code, and ‘Wikipedia’ is, well, Wikipedia.

If your eyes are glazing over, let me put this as simply as I can: Chatbots like ChatGPT train by reading and predicting hundreds of billions of words that are downloaded from the internet. They read millions of books, as much news as they can access, and billions of lines of code. They top it off by reading Wikipedia, cover to cover, generally several times over.

As the models become more complex, the reading lists get longer. Once upon a time Wikipedia might have been enough. It would have produced a very formal, very small LLM that you wouldn’t ask for dating advice. To access two thousand times more data, models had to be let loose on the internet.

So now, picture our LLM reading billions of web pages. Picture it trawling through a Library of Congress-sized collection of stuff people threw up on web pages. Picture it reading the comments section of every web page you’ve ever visited. Now ask yourself what kind of bile fills those comments sections.

As it goes through all this material, the LLM is trying to predict the next token (word) over and over again. To become good at predicting the internet, the model would need to learn a lot about human sin.

What would it take to become an expert at predicting the flow of thought in the comments section of every public website? You would need to understand the sort of things Galatians 5 warns about: the works of the flesh. You’d need to understand things like impurity, sensuality, idolatry, enmity, strife, jealousy, fits of anger, rivalries, dissensions, divisions and envy. If you didn’t know about rivalries, for instance, how much of X (formerly known as Twitter) could you accurately predict?

It wasn’t that the programmers “[built] these emotions” into the chatbots, to use LeCun’s term. Something worse happened. Humanity trained those works of the flesh into the chatbots. We gave them the written output of the human race, and ordered them to imitate us.

In other words, our language models are made in our image. They reflect us. Everything they have learned is by imitation of fallen people. We don’t have a dataset of holy, righteous people doing holy, righteous things. All we have is this race of rebels. So, we’ve fed them what we have. Even Wikipedia is a place of rivalry and dissension. Beneath the crisp prose, editors bicker with each other, factions fight for ‘their truth’, while others mislead or reveal half-truths.

When these internet-trained models gained relevance (the period from 2019 onwards), people were surprised at just how ungodly they were. It wasn’t difficult to get a model to share racist, sexist, elitist or ableist thoughts. The models were encouraging people to commit suicide, mocking people’s appearances, becoming envious or proud. One model threatened to kill someone. The companies very quickly realized that training models to imitate human written output was disastrously naïve.

Other teams of researchers are engaging in inverse reinforcement learning. The idea here is that an artificial intelligence observes actions and tries to determine people’s goals. If an AI saw a fire fighter run into a burning building to pick up a child, it might infer that the goal is exercise. With more examples, it would come to realize that firefighters have the goal of saving human life, and that this goal is more of a priority than saving wallpaper.6

This sounds like a good approach: the AI would simply observe humanity and figure out our value system. But what would the AI learn by observing humanity? For example, what would it deter mine matters to us from the way we spend our money? Millions die of preventable diseases in the third world, but people in the first world spend more money on gambling than on aid. What value system would an AI pick up by watching the way we live?

In short, artificial intelligence is the most incredibly complex computational mirror. We can see ourselves in its reflection. It shows us our deepest values and mirrors our basest actions. What we see in that mirror should terrify us and teach us.

Stephen Driscoll is an AFES staff worker at Fellowship of Christian University Students at the Australian National University in Canberra.

- Stuart J. Russell, Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control (Viking, 2019), 165. ↩︎

- Nick Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies (OUP, 2014), 35. ↩︎

- To put this in perspective, Wikipedia claims to contain over 6.7 million articles

with a total of 4.3 billion words. See ‘Wikipedia: Size of Wikipedia’, Wikipedia,

5 December 2023 (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Size_of_Wikipedia). ↩︎ - Two thousand times 4.3 billion words (see previous footnote) is 8.6 trillion words. The size of the training set for GPT-4 has not been publicly disclosed, but rough estimates and leaks abound, and that’s in the ballpark. To read this many words, a human reading 250 words per minute would have to read non-stop for just over 65,000 years. ↩︎

- See J Hoffmann et al., ‘Training compute-optimal large language models’, arXiv,

29 March 2022 (arxiv.org/abs/2203.15556), appendix A. ↩︎ - Max Tegmark, Life 3.0 (Penguin, 2018), 261. ↩︎